The world continues to take the pandemic increasingly seriously. We will spend many years discussing what we should have done, how many lives we could have saved if we had moved faster, responded quicker, or been more aggressive; but the world at large now accepts action as the only choice left to save lives. We now enter the hardest portion of the response: blind faith that the measures we enact today will pay dividends in the future. And a desperate search without sufficient data to guide us, for the best way to save as many lives as possible.

Where We Are

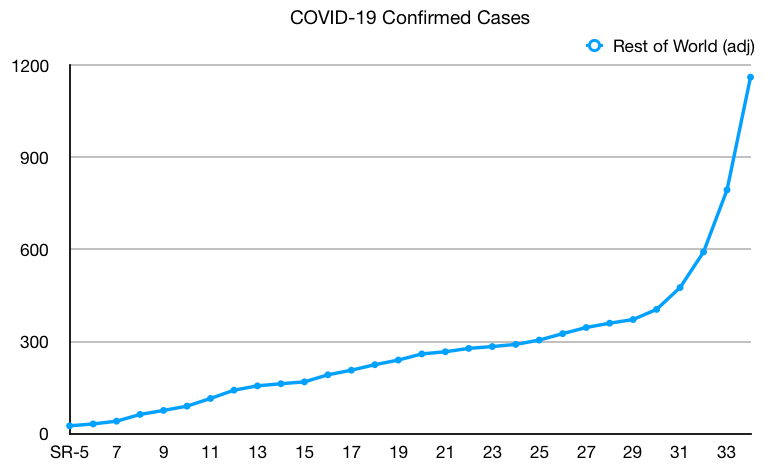

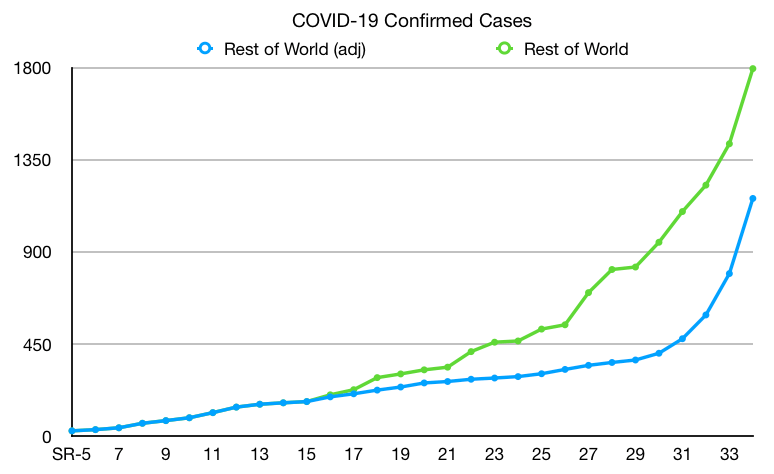

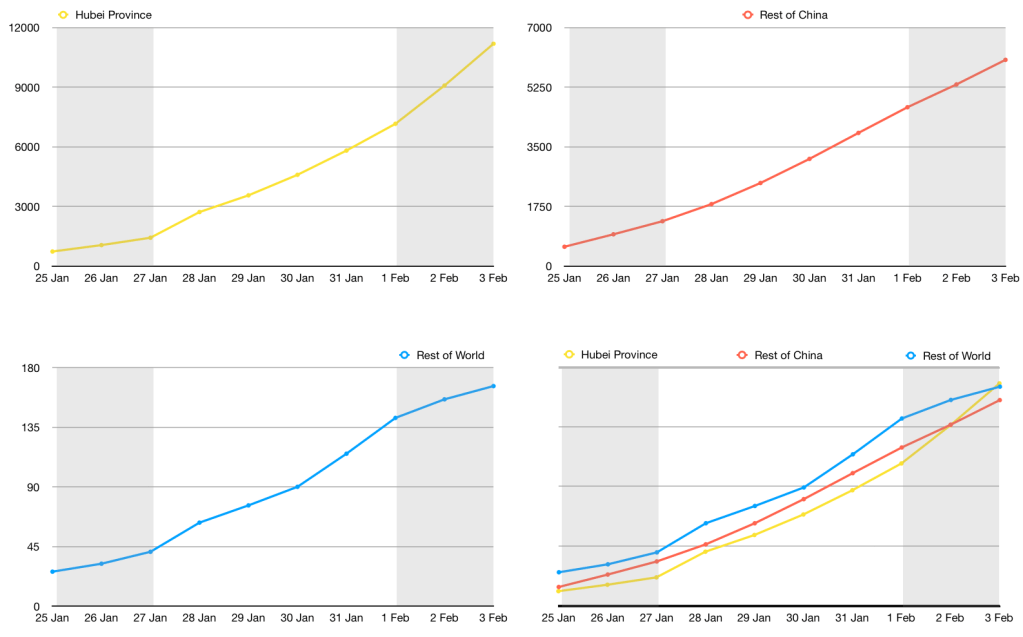

In the last post we discussed the epidemic curve we were on and how we would hope to see the projections lower if the measures countries were putting into place were successful.

Those projections were:

After I wrote the post last week, the model I used to generate these estimates jumped up by a small amount, taking it slightly past the upper projection and which then settled there. In the past seven days, the April 1st estimate has stayed within a tight 500 death range. The model now predicts that on April 1st, Situation Report 72 will list global fatalities as being between 42,500 and 43,200.

New Projections

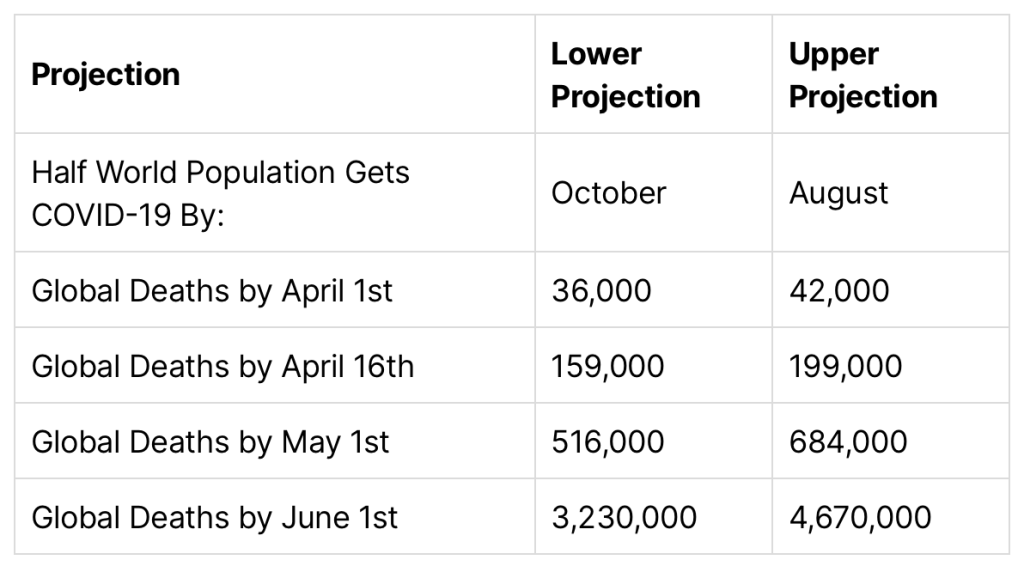

Here’s the full new table:

| No Change In Condition Projection | Conservative | Aggressive |

| Half of World Gets COVID-19 By: | October | July |

| Global Deaths by April 1st | 42,500 | 43,200 |

| … by April 16th | 172,000 | 208,000 |

| … by May 1st | 588,000 | 727,000 |

| … by June 1st | 4,530,000 | 5,100,000 |

Again, these are the projections of the curve we’re on. This assumes that our actions have no impact. Everything we know about COVID-19 tells us they will have an impact, and our behavior has a chance to take us off this curve and put us on a flatter one. While the last round of projections appear like they’re going to be accurate, they were only made a week ago. It will take several weeks for a new curve to show up in the fatality data that this model is based on. Hopefully we will see the April 15th data closer to, if not under, the more conservative estimate.

What if it Gets Worse?

If you don’t want to read a data driven argument on why these numbers might very well get worse even with everything we’re attempting to do, please skip to the next section.

It’s okay. Reading this or not won’t change the outcome. Skip ahead and see why these projections don’t really matter anyway and that we’re still doing a lot right.

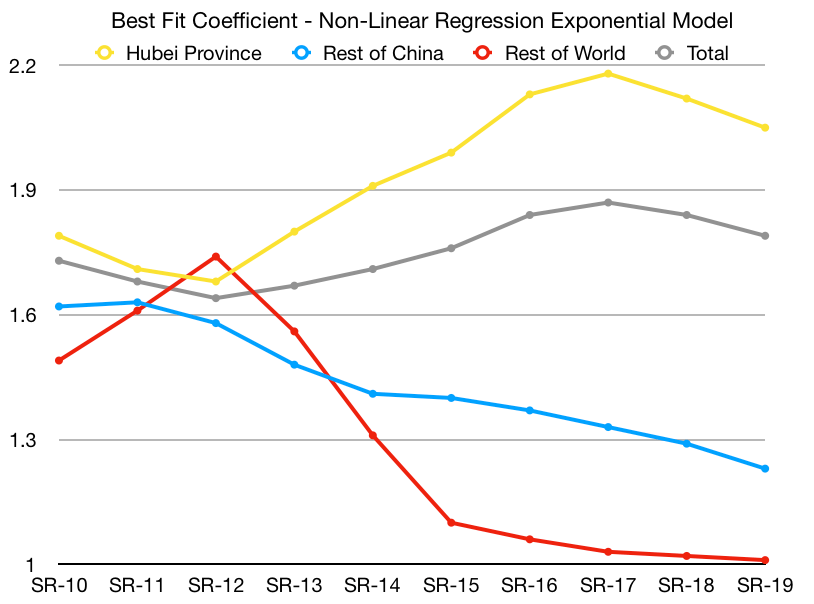

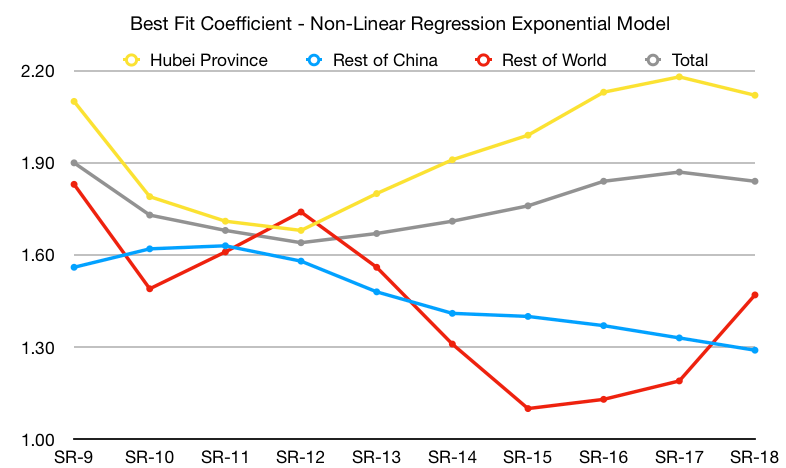

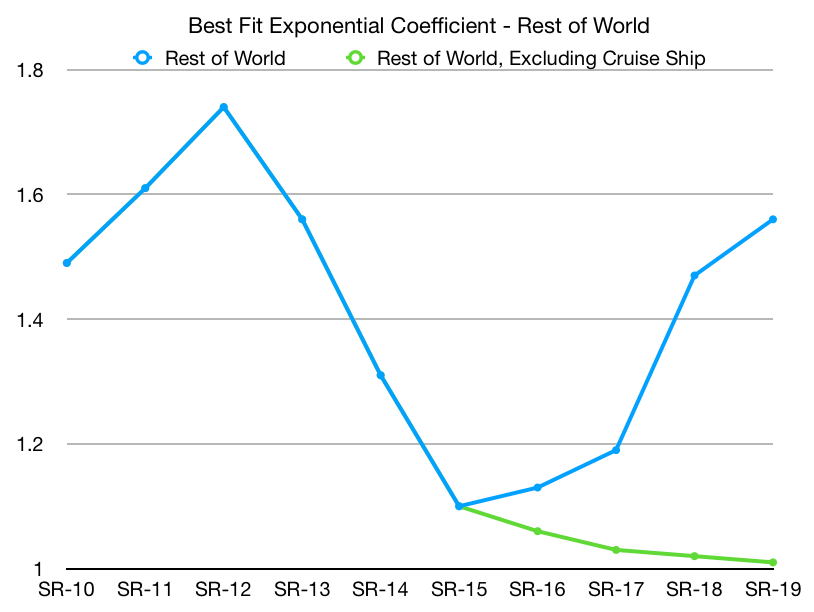

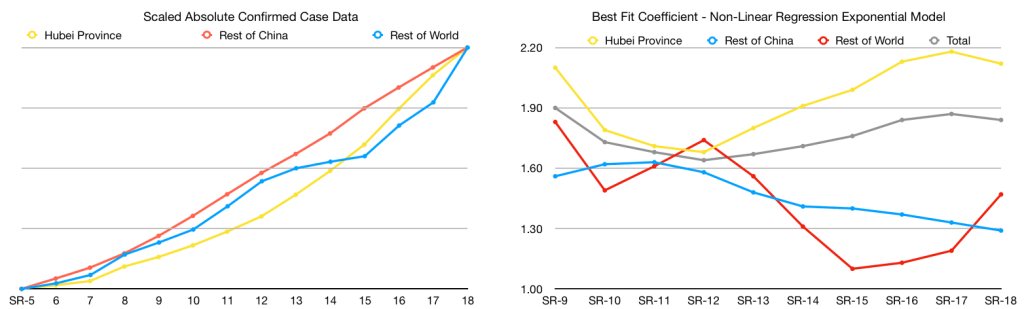

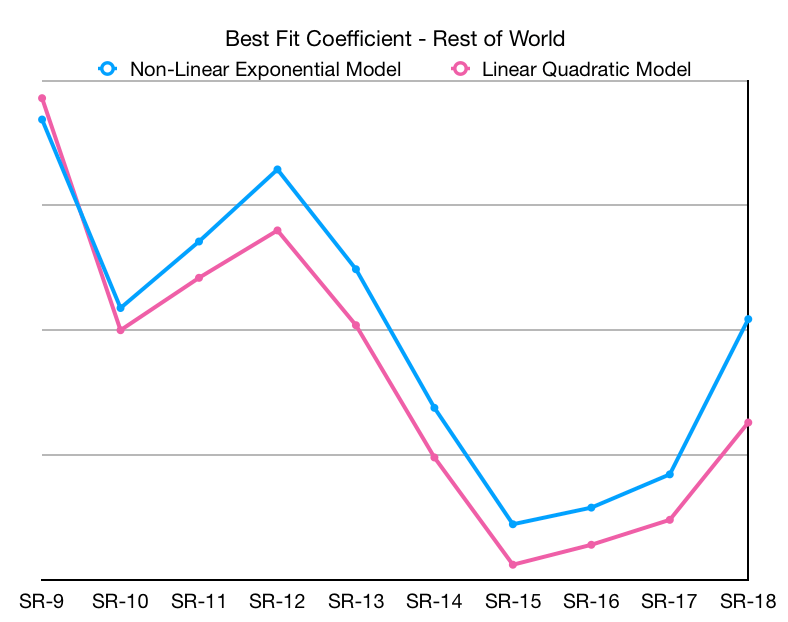

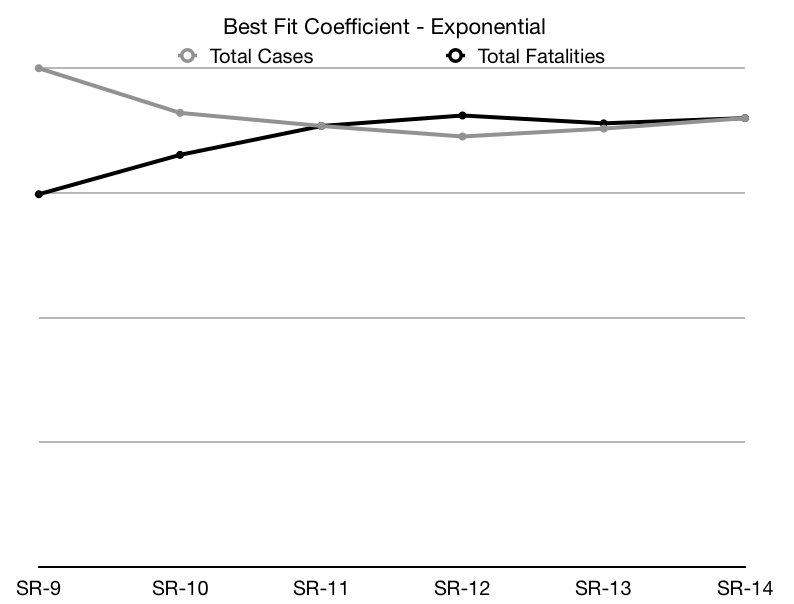

For everyone else, let’s start talking about the model we’re using. The model that generated the projections above is extremely naive. It essentially assumes that all of today’s conditions will remain the same and follows the exponential curve the fatality rates we’ve reported so far best fits to and extrapolates blindly. It is the stupidest model you can write and call it a projection.

Epidemiologists would rightly point out that this model is ridiculous since there are so many other factors in play. I agree with that sentiment entirely, but would respectfully suggest that we may be closer to having no clue on the correct numbers for those factors than we are to knowing the right values for them. From the other models I’ve seen from epidemiologists trying to study this so far (It’s been heartening to see folks finally releasing these! I have long been frustrated that I couldn’t find better data here and real projections! It’s why I started this blog!) are essentially making educated guesses based on some previous datasets and basically picking the constants that sound right to them. Which is a totally valid thing to do in the middle of a pandemic, and something epidemiologists have trained their entire careers to do. Picking constants is their prerogative and they are absolutely trained to do it better than anyone else.

But I’m going to keep blogging about what this stupid model says because I think there’s some merit in a completely stupid model. You see, with a stupid model, you expect it to be dumb. In a world of uncertainty the one reliable thing may be that these models are always dumb. They will never see changing conditions coming. So if they are stable, you can be certain conditions reflected by the data aren’t changing yet. And if they are unstable, you can be certain conditions are changing. No one would ever use this model to predict the outcome of an intervention, because it isn’t smart enough. And that’s fine, because if you want to predict human or biological behavior, you absolutely should ask an epidemiologist. They most likely won’t really know either, but they’re the most qualified people in the world to guess about it. And you should listen to their guesses, because they’re the best we have.

So. Back to our dumb model.

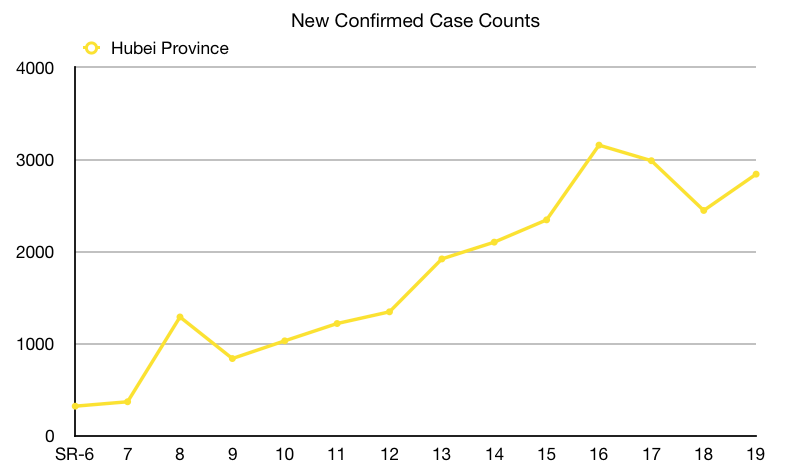

The projections above are all based on no change in conditions. There’s two different types of conditions that we expect are likely to change in the coming days, and they can each push the model in dramatically different directions:

The first is human behavior. We’ve covered this one most extensively and it’s where the most good news is to be found. Humans all over the world are doing so much, in so many ways to stop the spread of COVID-19. If you can stop having anxiety about this whole thing long enough to appreciate it, it is a rather inspiring moment of solidarity. One that is finally resonating worldwide.

The second is medical system capacity. Not to repeat myself too much but—this model is dumb. It doesn’t know anything about hospitals, ICU beds, staffing levels, or healthcare breaking points. These things are likely to provide an accelerated fatality rate when they start happening.

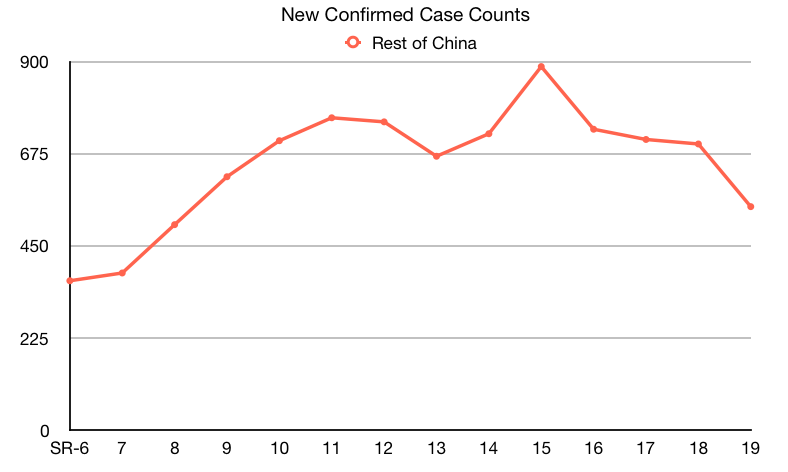

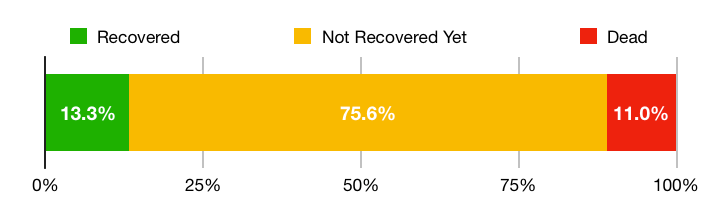

Italy is probably the country currently furthest along in this particular struggle. Here’s their current outcomes so far:

This is a hard graph. While we can arguably expect most of the 75% of the people who haven’t recovered yet to make a full recovery (95% of pending cases are currently classified as mild, though some of them will likely become severe later) an 11% fatality rate of all confirmed cases is a hard datapoint. There’s a few possible reasons we’re seeing such a high fatality rate here:

- There’s an order of magnitude more cases here that just haven’t been confirmed or had or will have successful outcomes without ever interacting with the medical system.

- Hospital resource prioritization means we’re only seeing the data for the most serious cases.

- The outcomes in Italy really are worse than elsewhere due to an overloaded medical system and we can expect to see elevated fatality rates in areas where healthcare systems become impacted.

The real story is likely a mix of these factors. But it’s the last bullet point that is the major reason we could have a lot more fatalities than the model currently predicts. Given what we know about the state of the Italian healthcare system, it is likely that while some of the other possibilities are likely playing a role in this data, healthcare system overload is likely showing up in the data as well.

To be very clear, this is not to say the Italian healthcare system is bad. They’re just handling more than almost any system could reasonably be expected to handle. Unfortunately the Italian healthcare system is comparatively good on a global scale, which means some countries with worse healthcare systems are likely to see even worse outcomes than we’re seeing in Italy.

What if We Don’t Succeed?

I think the most scary thing right now is the idea that we won’t bend the curve. That we won’t be able to stop this pandemic. Among everyone I know, these seems to be the thoughts that weigh heaviest right now. And there’s elements of truth to them. Ultimately only a vaccine or treatment protocol seems likely to stop the pandemic entirely.

But our actions today are still critical. Everything we are doing, everything any group of people on this planet tries to slow the spread, is worth lives. Whether it’s washing your hands, wearing a mask, social distancing, or locking down entire cities. It’s all important. And it will help save lives. Either by slowing the spread down to give our hospital systems a little more time, or by slowing the spread down to give us time to develop treatments or a vaccine. Every action we take to slow the spread helps.

It ultimately doesn’t matter whether we go above or below these projections. What matters is that when it comes down to decisions that allow us to slow the spread of COVID-19, we chose to act. And ultimately that’s the only thing we can do. And that’s the track and outcome that saves as many lives as possible. Each of us can make that decision for ourselves, and help as many people around us as we can.

As long as we do all we can, we can’t fail.